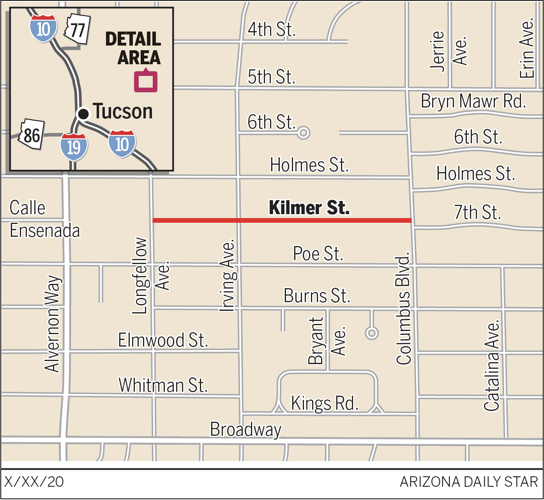

A Tucson street is named for Joyce Kilmer, the poet famous for penning “Trees” — “I think that I shall never see / A poem lovely as a tree ...”

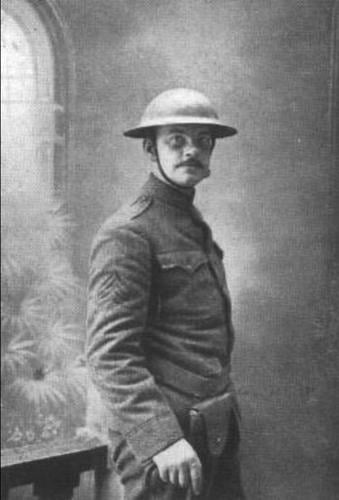

Alfred Joyce Kilmer, more commonly known as Joyce Kilmer, was born to Episcopalian parents, Dr. Frederick and Annie (Kilburn) Kilmer, on Dec. 6, 1886 in New Brunswick, New Jersey. His father was the inventor of Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder.

Kilmer attended Rutgers Preparatory School where he was editor of the school paper and spent many summers with his mother in England.

This was followed by his studies at Rutgers College and Columbia University in New York City; he graduated from the latter in May 1908.

The following month he married Aline Murray, stepdaughter of Henry Mills Alden, editor of Harper’s Magazine, who was from the nearby village of Metuchen, New Jersey, and they would go on to have a few children. She also later authored several books of poetry and children’s stories.

He went to work teaching Latin at Morristown High School in Morristown, New Jersey, and moonlighting as a writer of reviews, essays and poems. Over the next few years he became a famous editor, journalist and literary critic.

The couple moved to New York City where he was employed defining words for The Standard Dictionary at Funk and Wagnalls.

His first volume of poetry, entitled Summer of Love, was published in 1911 and featured poems about George Meredith, English novelist and poet, and Florence Nightingale, the famous nurse and social reformer, both of whom had recently died.

In 1912, James Daly, a Jesuit priest and English professor at Campion College in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, penned a letter to Kilmer to talk about literature. Kilmer and Daly corresponded and in time developed a close friendship. This relationship led Kilmer and his wife to convert to Catholicism the next year.

That same year, in 1913, Kilmer joined the staff of The New York Times and scribed his most famous poem and the work he is most well-known for, “Trees,” which first appeared in Poetry magazine:

“A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree”

The following year a compilation was published in book form as Trees and Other Poems.

Kilmer wrote several other books as well, including The Circus and Other Essays in 1916 and Main Street and Other Poems and Literature in the Making, both in 1917.

He also edited Dreams and Images: An Anthology of Catholic Poets. Among these verse writers he wrote about were four Jesuits and he dedicated the volume to Father Daly.

When the United States entered World War I, Kilmer, then a well-known literary figure in the country, chose to sign up as a mere private in the Seventh Regiment of the New York National Guard.

In time, he requested help from Father Francis Duffy, the regimental chaplain, of the famous New York City “Fighting 69th” infantry regiment to transfer to his body of soldiers. The bard and priest became fast friends.

Kilmer was also aware that his enlistment would bring difficulties for his wife:

“I feel the pain of my sacrifice is hard on both of us, but I realize also that God wills me to do my duty in this manner and, therefore, I have every reason to believe that He will take better care of my wife and children than I should ever hope to do. I have considered this step I am taking from every side and I feel there is no doubt that I have an obligation to join the colors. I would be ashamed later on to look at the children if I don’t volunteer. However other married men feel about going, I consider my enlisting as a duty I owe to God and country.”

The Fighting 69th had a proud record of service in the U.S. Civil War, during which, according to legend, the military unit obtained the title “Fighting” from one of the most revered military generals of the time, Robert E. Lee.

Kilmer ascended the ranks quickly from private to sergeant and was soon after offered a commission as an officer if he was willing to transfer out of the Fighting 69th, at that point known as the 165th Infantry Regiment. The poet-soldier declined, saying he would rather be a sergeant in the 69th than an officer with another regiment.

Before leaving for the war, he experienced both heartbreak and felicity in a short period of time: His daughter Rose died and less than two weeks later his son Christopher was born.

His first job in the conflict was as a statistician, a “bullet-proof” job, as he called it, away from the action. Since this wasn’t why he signed up, he transferred to the regiment’s intelligence section and earned a reputation for his fearlessness on scouting missions against the front lines of the enemy forces.

On July 30, 1918, Sgt. Kilmer was scouting ahead of the other soldiers to try to locate German machine gun positions near the Ourcq River when he was shot and killed by a German sniper.

He was awarded the Croix de Guerre posthumously by the French government.

Frank H. Spearman, a fellow writer, shared his thoughts in the Los Angeles Times on Kilmer’s sacrifice soon after his death:

“Joyce Kilmer’s patriotism contained not even the alloy of ambition — it was refined gold. And it is for this — for his taking his place lowest at the table, for his modesty in choosing the simplest and most obscure service in the great army and walking straight to the trenches —that I lay this little wreath on the grave of a gentleman unafraid and a patriot undefiled.”

In 1930, in Tucson, Evo DeConcini, the future Arizona Supreme Court justice and namesake of the Evo A. DeConcini Federal Courthouse in downtown Tucson, recorded the Colonial Estates subdivision, which included Kilmer Street.

The subdivision’s naming streets after writers and poets was a continuation of street naming that began with J.M. Roberts a few years earlier in the nearby Country Club Heights subdivision.