Lew Davis, a Pittsburgh-born real estate developer turned political leader, had been mayor of Tucson less than 30 days when he uttered the remark that would create enduring national notoriety for the Old Pueblo.

The date was Jan. 2, 1962, the location, the City Council chamber, and the event, a pre-council meeting. The mayor was expressing to local media and others his concern about the dangerous driving habits of some Tucsonans along the city’s main business thoroughfare.

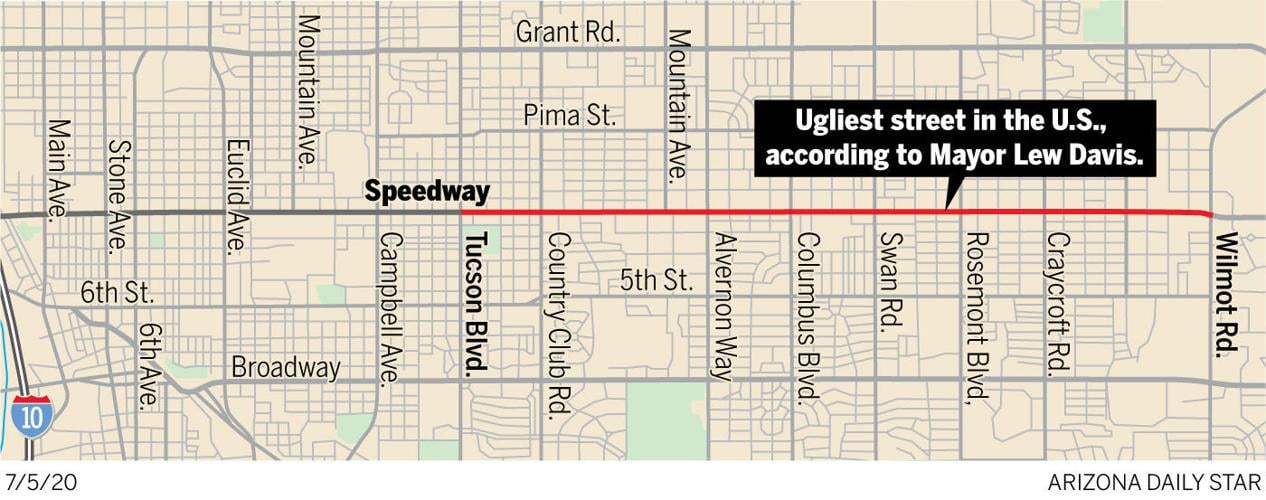

“East Speedway is the ugliest street in the U.S.,” he said.

Former Tucson Mayor Lew Davis first called Speedway “the ugliest street in the U.S.”

“That was my daddy,” Andrea Davis recently related. “Definitely not a ‘politician,’ he did things his own way, was always forward-thinking and wanted the best for all. His statement almost certainly was intended to draw attention to the problem in order to get something done about it.”

A little over a week later, the Arizona Daily Star published an editorial with the headline “The Ugliest Street in the U.S.,” confirming Davis’ assertion and going a little further by defining “East Speedway” in this usage as “approximately Tucson Boulevard on” to Wilmot Road.

It gave an explanation for the displeasing nature of Speedway, or Speedway Boulevard — the “boulevard” had been added four years earlier because the street’s merchants believed the name “Speedway” by itself led to fast driving.

Many years of poor city zoning were to blame, the editorial said. Hodge-podge development along the route consisted of ugly buildings, grotesque neon signs and “hazards to life and limb.” But the Star lamented that probably nothing could be done since it would cost more to correct things poorly done than to have done them correctly in the first place.

In the February 1962 issue of Arizona Architect, a trade journal for registered architects, the editors chimed in with their opinion on the deplorable effect of Speedway’s overabundance of large signs — free standing and building mounted — as well as inadequate setbacks of buildings and unattractive structures along the boulevard.

“In a recent statement,” the article said, “Mayor Lew Davis of Tucson called East Speedway, in his city, the ugliest street in America. The appellation was an exaggeration and one that Phoenix could easily challenge, by offering Camelback Road in evidence. Nevertheless, that statement was a healthy sign and resulted in an increased public awareness of the lack of planning and ‘housekeeping’ on this busy thoroughfare.”

The article went on to share some progress in improving the situation and stated what else needed to be done: “The Planning and Zoning Commission has approved a street setback ordinance which will allow for easier widening of streets in the future and an architectural approval board, consisting of two registered architects and a building inspector. ...

“Now if serious attention will be given to a law prohibiting freestanding signs and otherwise controlling height, setback and other factors of billboards, Tucson will do much to make itself the beautiful city in a beautiful setting that it could be.”

Speedway earned its nickname, in part, for its once endless row of neon signs, inadequate setbacks and unattractive buildings.

Apparently, however, the changes made the previous year did little to improve things and a sullen Speedway exacted her revenge, compiling a total of 59 accidents on her pavement for the month of January 1963 and leading the traffic division of the Tucson Police Department to label it “the most dangerous street” in the city.

The changes also did little to stop the unsightly neon signs. The following month, Arizona Neon Advertising Inc. unveiled what it proclaimed was the largest “wipe-on” (vertical louvers that open and shut) neon sign in the state. This Arizona Brewing Co. neon sign measured 16 by 43 feet and consisted of more than 1,200 feet of glass tubing and 1,120 light bulbs and found its home, where else, but on East Speedway near Country Club Road.

In response, one reader wrote to the Star, exclaiming, “It seems Speedway, not satisfied with being our ugliest street, now wants to beat everyone in another way. Maybe this monster billboard will awaken those desiring billboard restraint to the fact they haven’t reached their goal yet.”

Despite the negative press, one small-business man, Tom Bahti, owner of Tom Bahti’s Indian Arts and Crafts Shop at 1706 E. Speedway, found it useful in advertising his store. In one of his advertisements after he listed his address, he wrote: “The ugliest street in America says Tom.” A few years later he finished another ad with “America’s ugliest thoroughfare.”

“Dad had a keen aesthetic sense,” said his son Mark Bahti in a recent email, “appreciative of everything that constituted good design in Tucson, as well as a great sense of humor. So the one-liners in his ads were a way of making a point while drumming up some business.”

In April 1963, Davis, debating an attorney during a council meeting on the need for building setbacks from the street, upped the ante to: “It’s the ugliest street in the world.”

Soon after, Don Schellie, a longtime columnist for the now-defunct Tucson Daily Citizen newspaper, asked whether East Speedway Boulevard was not the ugliest street in America but just the “ugliest street in town.”

Schellie wrote: “A beautiful boulevard that MIGHT have been. Instead, an avenue of purple-painted supermarts, faded-flagged used car lots, weed-covered empty spaces, all bathed in flickering neon.

“East Speedway, where a few nice business places hint at what might have been. East Speedway, where junk and trash show what so much of it is. Heaps of rocks and stones for sale; an orange-painted mailbox; a pyramid of empty oil drums in front of a hardware store. Garbage and trash cans in front of stark, unpainted concrete shops.

“Storeyard for a plumber; a scatter of second-hand toilet bowls, wash basins, bathtubs, seats and water heaters, just a few disgusting feet from the pavement. And out back, an ugly, gray corrugated metal shed.”

Schellie offered up his own name for Speedway Boulevard: “Eyesore Avenue.”

Two months later, Schellie’s comments led to an amusing response. He received this letter:

“Our board carefully noted the comments you made on ‘the purple and white building on Speedway’ and since our board is always on the alert for special meetings (which are at company expense), we adjourned to Miami (Fla., not Ariz.) and contemplated your criticism while sipping mint juleps and studying new bathing suit styles. As a result, we decided to paint the exterior of Kal Rubin City (retail store) chalk white.

“We hope this decision meets with your approval. The paint job cost $1,100, while our board meeting cost us $8,356.75. Our board, I may say, is very pleased that you offered the comments at the time of year when Miami is most pleasant.

Speedway looking east near Country Club Road in December 1957. Note the Ryan-Evans Drugs on the corner at right. The store was originally owned by the Martin family. George A. Martin Sr. established a pharmacy inside the walls of the Tucson Presidio in the 1880s. His sons expanded the business throughout Tucson.

“We regret to say that we did not discuss the interior of the store, which has a touch of violet here and there. If you have any comments on this, would you please reserve them for October.”

Just a couple years later, though, Tucson’s City Council wasn’t so sure how hideous the street was and set up a meeting to discuss the issue.

Ben H. Solot, a former president of the Speedway Merchants Association, appeared at the meeting and requested Mayor Davis “refrain from calling Speedway ugly” in public. He was challenged on the other side by Jerry Alpert, the president at that time of the Speedway Merchants Association, whose position was contrary to Solot’s.

The meeting wasn’t a complete waste, despite the standoff, since the council did decide to widen Speedway from Alvernon Way to Craycroft Road.

In May 1965, Sidney Little, dean of the University of Arizona College of Architecture, challenged the Speedway Merchants Association to beautify one block as a pilot project.

“With the proper publicity,” he said, “I’ll lay you even money that within a year other blocks on East Speedway will cooperate and join the fight to keep Speedway from staying the ugliest street in town.”

The association’s 40 members voted unanimously to support the idea and recommended an unspecified block between Country Club and Swan roads.

In September 1965, the merchants announced preliminary plans for the beautification of a three-store zone — instead of a whole block — just west of Swan Road. A landscape man and architects were hired, but a year after the original challenge, little more than talk had been accomplished — although the widening of Speedway and additions of median strips with plants had happened in the meantime.

By November 1965, Tucsonans had already heard Speedway designated as “the ugliest street in town, in America, in the U.S. and in the world,” but would soon learn of its insidious effect on the city’s wayward youths.

Charles H. “Smitty” Schmid Jr. was a misfit who had been in the newspaper a few months earlier for receiving a 30-day jail sentence for racing another driver on a small street near Speedway. Now, his name was again in the Arizona Daily Star, this time on the front page. He was accused of murdering his girlfriend, her sister and possibly another teenage girl.

Murderer Charles H. Schmid Jr. brought more notoriety to the street and Tucson.

Although Speedway’s connection to Schmid and his group escaped public shaming in the local newspaper, it wasn’t too long before it began to surface above the paved streets.

Later in the month, Schmid and this shocking case would gain national attention when Time magazine on Nov. 26, 1965, featured a story titled “Secrets in the Sand.” It began: “To the bored, vacant-eyed teen-agers who hang out at the drive-ins and juke joints along Tucson’s East Speedway Boulevard ...”

In March 1966, Time once again covered the legal case in a piece called “Growing Up In Tucson,” this time writing: “Among the odd collection of restless, thrill-hungry teen-agers who hang out in the garish juke joints and drive-ins along Tucson’s East Speedway Boulevard ...”

The same month, Speedway took another hit to its tainted reputation in a Life magazine story written by Don Moser — later editor of Smithsonian magazine — titled “The Pied Piper of Tucson.” The story covered Schmid’s life and utilized Speedway’s nightlife as the backdrop for Schmid and his friends’ teenage wasteland:

“At dusk in Tucson,” Moser wrote, “(Schmid’s) golden car slowly cruises Speedway. Smoothly it rolls down the long, divided avenue, past the supermarkets, the gas stations and the motels; past the twist joints, the sprawling drive-in restaurants. ... The driver shifts up again through the gears and the golden car slides away along the glitter and gimcrack of Speedway. Smitty keeps looking for the action.

“After his (school) suspension ... he haunted all the teen-age hangouts along Speedway, including the bowling alleys and the public swimming pools.”

“Of an evening kids with nothing to do wind up on Speedway, looking for action. There is the teen-age nightclub (‘Pickup Palace,’ the kids call it). There are the rock n roll beer joints where they can Jerk, Swim and Frug away the evening to the room shaking electronic blare of ‘Hang On Sloopy,’ ‘The Pied Piper’ and a number called ‘The Bo Diddley Rock n’ Roll.’

“Here on Speedway you find Richie and Ronny, out of work and bored and with nothing to do. Here you find Debby and Jabron, from the wrong side of the tracks, aimlessly cruising in their battered old car looking for something — anything — to relieve the tedium of their lives. ... Here you find Gretchen, pretty and rich and with problems, bad problems. Of a Saturday night, all of them cruising the long bright street that seems endlessly in motion with the young. Smitty’s people.”

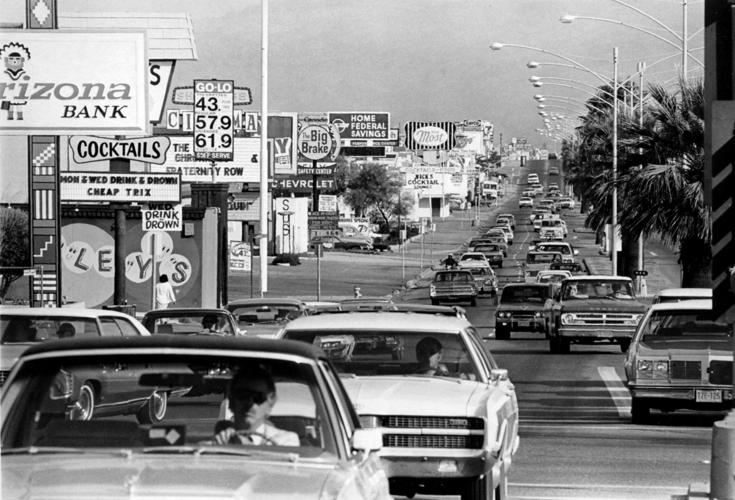

The article also featured an image of Speedway at night, taken by Bill Ray — best known for his pictures of legends such as Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe and the Beatles — with its never ending row of neon signs, clogged lanes and structures that appeared to have no space between them.

Moser wrote of the photograph, “On The Neon Trail: This is Tucson’s Speedway Boulevard, a garish stretch of hamburger palaces and juke joints — the favorite world of Smitty and his crowd.”

Moser referred to Schmid as the “Pied Piper of Tucson,” a reference to the popular song of the time and because the killer had many followers in Tucson, whom he led down a dark path.

Schmid was eventually convicted of murder, sentenced to death, had his sentence commuted to life, and was fatally stabbed by fellow prisoners.

The national magazine articles about the case drew ever more attention to Speedway’s faults. By 1969, it appeared city officials were beginning to see that not only Speedway but much of Tucson was becoming “a monotonous large city which is destroying the beauty of its environment.”

The city’s Community Development Department undertook a study to decide what could be done to change the image of Tucson in general. The result was a booklet titled Tucson Visual Environment, although it appears not much came out of the study.

In July 1970, Life — at the time a very popular magazine — featured an article called “Look Down, Look Down, that Loathsome Road,” and featured a large color photograph of Speedway at Country Club splashed across the first two pages.

“The view down ‘The Speedway’ in Tucson supports the mayor’s opinion that it is America’s ugliest street,” it declared.

The mayor by this time was no longer Lew Davis but Jim Corbett, and not having said the phrase, Corbett correctly denied it.

That led many to just credit Life magazine as the source of the phrase — which Tucsonans and the local media have repeated incorrectly time and time again.

Photos: Speedway Boulevard in Tucson through the years

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Once dubbed America’s “ugliest street” by Life magazine is Speedway Boulevard looking east from Alvernon Way . photo taken by: Jose Galvez December 15, 1977.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Sitting in the Oldsmobile is Beverly Smith Hansen (McClung), a 41 year-old, mother, model and artist. This Blakely's Service Station was on East Speedway near Kiddyland Amusement Park. The photo was used for an advertisement in the late 1950s.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

What is that contraption at the counter? It's called a cash register in this Sept. 1982 photo inside the McDonald's Restaurant at Speedway and Campbell.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Work crews remove the infamous "hump" from the middle of Speedway Blvd., on September 12, 1957.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The Empress, 3832 E. Speedway, shown in 1988, had been in operation since 1971 and was Tucson's longest-operating adult store.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Bill Rauh Sr. owned Wilson's Bakery at the northwest corner of East Speedway and North Park Ave. in the early 1950s. Bill at one time made a promotional cake for Pet Milk, canned milked, and Softasilk, a brand of flour, as they tried to break the record for the world's largest cake Wilson's was one of three bakeries in Tucson at the time. Bill made wedding cakes for all six of his kids.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Consumers East Speedway Market. 1953

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

An undated photo of the Dorado Country Club on East Speedway, east of Wilmot Road while under construction. Tanque Verde Road cuts diagonally across the photo towards the Pantano Wash. The 18 hole executive length course was originally designed by Ted Robinson, ASGCA, the Dorado golf course opened in 1970.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Swank western layouts like this one at Tanque Verde Guest Ranch (now Tanque Verde Ranch) at the end of East Speedway Blvd. were a big magnet for winter visitors in 1965.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The Speedway Blvd "Hump" in 1953.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The $1 million in bond funds recommended for street lighting would put lights like these on East Speedway on about 20 miles more of busy arterial streets in 1965.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

This 1922 photo shows the empty desert stretches out beyond the 40-acre University of Arizona campus. The buildings identified are (1) Engineering College, built in 1919; (2) Old Main, built in 1891; and (3) Cochise Hall, a dormitory built in 1922. Today the campus has expanded to 180 acres from Park Avenue area to Campbell Avenue. Speedway cuts diagonally across the pictures. The intersection of Speedway and Campbell is marked.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The Orielly Chevrolet Used Car lot, on 3313 E Speedway Blvd., had plenty of lights to display their vehicles on July 31, 1972. El Rancho Market grocery store and the Thom McAn shoe store is visible in the background.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Children bite the ice at Iceland, 5515 E. Speedway Blvd., in 1985.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

A birthday appears to be underway at Kiddyland, 3943 E Speedway near Alvernon on Dec 1962. In the era before television Sam and Ruth Cohen opened Kiddyland in 1949 and operated the playland for children until 1958. They had a Ferris wheel, roller coaster, train, cars on two-and-a-half acres. By 1962, Luverne Hicks took over the operation and had 10 mechanical rides and for a flat rate of $11.85 a birthday party of eight could be entertained with cake, ice cream, party favors, and eight rides apiece. At the time of the 1962 article, Hicks had hoped to move the operation to what was then, Randolph Park. Apparently, it did not work out.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The 150-room Plaza International Hotel on the corner of North Campbell Avenue and East Speedway Boulevard, close to the University of Arizona, nears completion on March 18, 1971.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The new Gil's Chevron Service Station at 203 E Speedway on the northeast corner at North Sixth Avenue was open for business in March 1968. The photo is looking toward the southeast.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Interstate 10 under construction at Speedway Blvd. in October, 1958.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Speedway Blvd looking east from Alvernon Way in Tucson, ca. 1980. Note the Showcase Cinema at left. It's now The Loft Cinema.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Night traffic along East Speedway east of North Country Club looking east on July 31, 1972.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Speedway Boulevard, Tucson, looking east from near County Club Road in December, 1957. Note the Ryan-Evans Drugs on the corner, at right, originally owned by the Martin family. George A. Martin Sr. established a pharmacy inside the walls of the Tucson Presidio in the 1880s. His sons expanded the business to cover Tucson.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Pedestrian underpass under construction under Speedway and Warren on the University of Arizona campus on Sep. 11, 1990

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

Interstate 10 (reffered to as the "Tucson freeway" in newspapers at the time) under construction at Speedway Blvd. in the early 1960s. By Summer 1962, completed freeway sections allowed travelers to go from Prince Road to 6th Ave. The non-stop trip to Phoenix was still a few years away.

Speedway Boulevard in Tucson

Updated

The bar at the Twin Flames, 5150 E. Speedway, in Oct. 1955, which featured a landscape painting behind the bar and what looks to be a pretty good selection of liquor. It's now a car wash.