After more than two years of legal wrangling, hearings on a wide-ranging federal labor complaint against longtime Tucson-area copper producer Asarco LLC have finally kicked off — even as the company and its unions have returned to the bargaining table to work out a new labor contract.

The National Labor Relations Board launched hearings last week on a fifth amended complaint brought by regulators, based on charges leveled at Asarco by the United Steelworkers and six other unions representing about 1,800 workers in Arizona and Texas.

In multiple charges filed with the NLRB since 2020, the unions alleged that the company had engaged in “unfair labor practices,” including bad-faith bargaining, unilaterally changing work terms, disciplining and discharging employees for union activities and refusing to reinstate workers after a nine-month strike that ended in July 2020.

The NLRB agreed, and in June 2020 issued a formal complaint against Asarco, seeking a judgment that actions by Asarco constituted “unfair labor practices” that led to the 2019 strike.

Among other things, such a finding would entitle striking workers to get their jobs back, require Asarco to negotiate a new basic labor agreement and prompt the company to retract any changes deemed unlawfully implemented by the company.

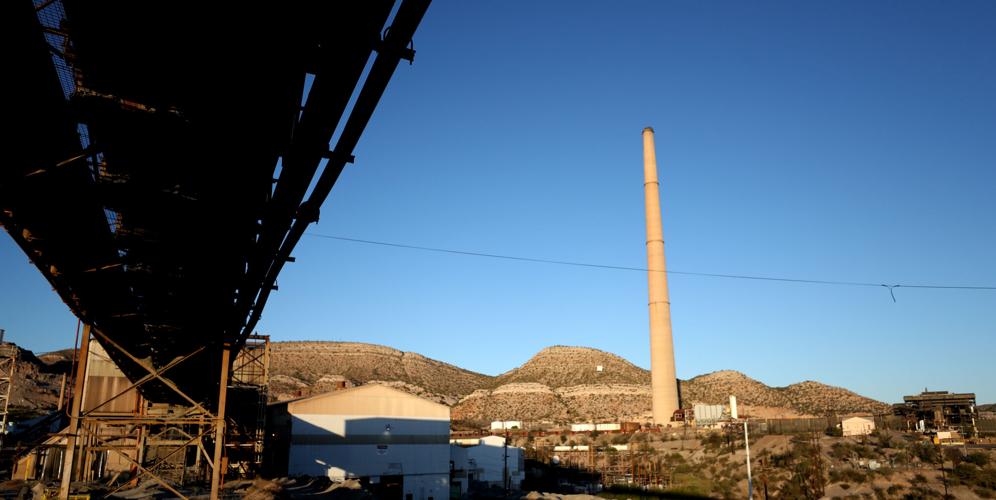

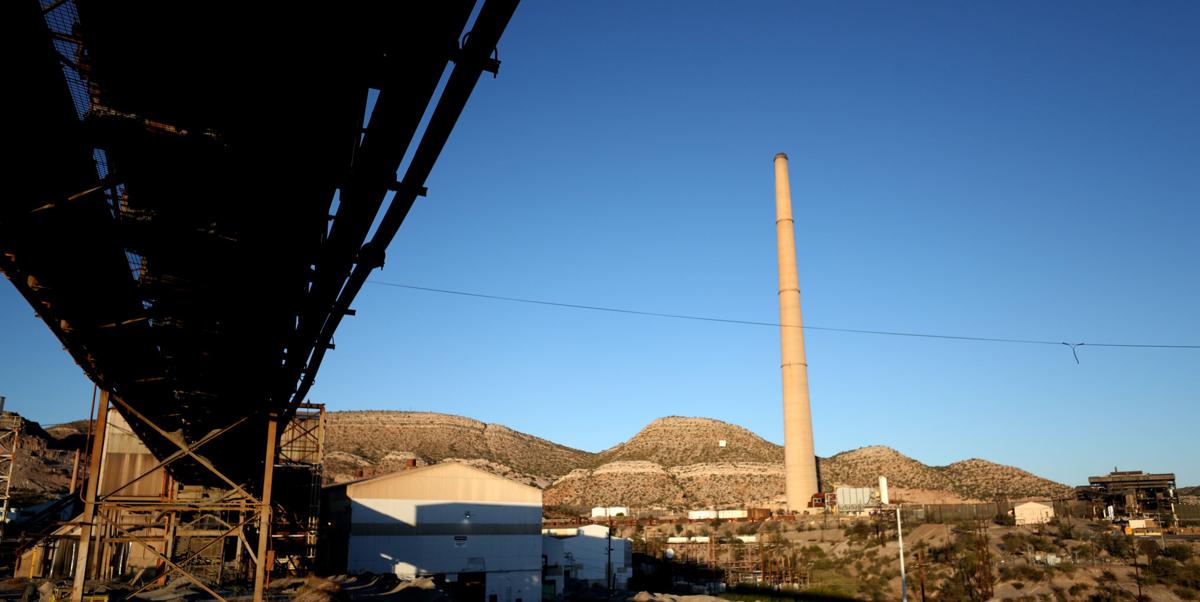

Asarco, owned by Mexican mining giant Grupo Mexico, operates the Mission Mine in Sahuarita; the Silver Bell Mine near Marana, the Ray Mine and Hayden smelter in central Arizona; and a copper refinery in Amarillo, Texas.

Grupo Mexico has a long history of labor strife including violent strikebreaking at Mexican mines, as well as a record of environmental violations.

Asarco in filings with the NLRB has denied any wrongdoing and contends the strike was based on economic issues, which would limit strikers’ rights. The company has ignored repeated requests by the Star to comment on the case.

NLRB attorneys began arguing their case in hearings before NLRB administrative law Judge Sharon Steckler, who after hearings scheduled to last into next year will issue a ruling subject to review by the full NLRB.

Bad-faith dealings

At an initial, online hearing on Aug. 19, NLRB attorney Chris Doyle accused Asarco of “having no intention of bargaining in good faith” for a new collective bargaining agreement to succeed a prior labor contract extension that expired in November 2018.

Doyle also said Asarco unilaterally implemented its “last, best and final” contract offer in 2019 and acted in violation of the National Labor Relations Act before and after that move, including limiting payment of a worker bonus paid based on the price of copper.

The copper price bonus itself became a major issue when Asarco sued to overturn a ruling by a federal labor mediator that it owed hundreds of workers back bonuses because they were improperly excluded from the bonus program.

After two federal district court rulings and an appellate ruling in favor of the unions, and denial of review by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019, Asarco paid more than $10 million in price bonuses to current and former workers.

Negotiations for a new contract started around August 2018, Doyle said in the NLRB’s opening statement.

“But respondent’s (Asarco’s) actions made it clear it had no intention of reaching a successor basic labor agreement with the unions,” he said.

For example, Doyle said, Asarco representatives showed up late for meetings, canceled agreed-upon meetings at the last minute, unreasonably delayed providing information the unions needed to bargain, and insisted on proposals it knew the unions would reject.

When Asarco declared an “impasse” in negotiations and implemented its final offer in December 2019, the company hadn’t provided the unions with the information they requested, he said.

Silver Bell was the subject of the most recent charges leveled by the unions against Asarco. In June, the Steelworkers filed NLRB charges that Asarco had illegally withdrawn recognition of the union at Silver Bell, contending it had no objective evidence the union had lost majority support.

“There was no impasse — the unions were still willing to negotiate,” Doyle said, citing a recent NLRB ruling that if either negotiating party is willing to move forward, no impasse can exist.

Away from the bargaining table, Asarco also violated federal labor law in its treatment of striking workers, Doyle said.

At the outset of the strike in October 2019, he said, the company sent letters to union members with instructions on how to resign from their unions and rescind their union dues payroll checkoffs.

Asarco also hired a private security firm to conduct surveillance on strikers, Doyle said.

After the Steelworkers and other unions ended their strike and offered to return to work unconditionally, he said, Asarco refused to reinstate some 800 strikers or displace the replacement workers they hired shortly after the strike began.

Asarco did hire back some strikers, but only if they agreed to work under the company’s final offer, and many who returned were not offered their former positions, Doyle said.

Many strikers remain on Asarco’s preferential hiring list but have not been rehired, he added.

Asarco also cut union positions at its Amarillo refinery in September 2020 to discourage union activities and shifted workers to jobs they were not trained for and assigned supervisory workers to union jobs, in violation of prior labor agreements, Doyle said.

Union members who returned to work at Asarco often were subject to “harsh discipline,” Doyle said, citing the dismissal of a haul-truck driver at the Mission Mine after a minor traffic violation, while non-union members were not fired for similar infractions.

At the Ray Mine Complex, two union members were fired after raising safety concerns about a new requirement that workers walk from a parking lot to the mill site, he added.

Asarco declined to make an opening statement at the initial hearing but will make one later as it makes its case, company attorney Richard Russo told the judge.

Testimony begins

In-person testimony in the Asarco case began Monday, Aug. 22, in central Phoenix.

The first witness was Asarco’s director of human resources, Stacy Sinele, who was quizzed by NLRB attorney Nicholas Gordon about the company’s operations and various documents, including correspondence between the company and the unions at the outset of negotiations in August 2018.

Asarco has about 1,400 total employees, down from about 2,300 in 2018, she said.

About 1,270 Asarco workers are represented by unions that besides the Steelworkers include the Teamsters and unions representing operating engineers, machinists, boilermakers, pipefitters and electrical workers, Sinele said.

The number of union-represented workers is down from around 1,700 in 2018, she said.

At its Tucson-area mines, Sinele said, the Mission Mine and milling complex employs about 500 workers, down from 600 in 2018, with about 480 represented by unions.

The Silver Bell Mine employs about 175 people, down from about 200 in 2018, when about 150 were union-represented, she said.

Silver Bell was the subject of the most recent charges leveled by the unions against Asarco. In June, the Steelworkers filed NLRB charges that Asarco had illegally withdrawn recognition of the union at Silver Bell, contending it had no objective evidence the union had lost majority support.

Elsewhere, Sinele said Asarco has about 500 workers at its Ray Mine near Kearny in Pinal County, down from about 600 in 2008, and another 400 at its nearby Hayden copper smelter and concentrator operation.

Sinele, who said she joined Asarco in 2014 as a community relations manager, figures prominently in the case as an Asarco lead spokesperson in the negotiations and for her part in correspondence over document requests and communications with employees.

The unions and NLRB have charged that Sinele sent letters to Asarco employees in October 2019, soliciting the revocation of employees’ checkoff authorizations for union dues and resignation of their union membership, in violation of federal labor law.

In its answer to the NLRB complaint, Asarco said the union “was provided with copies of the letters in advance and did not object to the transmittal of the letters to employees.”

The unions and NLRB also charge that Asarco managers denied some employees requests to be represented by unions, disrupted union activities and threatened union members with staffing cuts and “unspecified reprisals” for engaging in protected union activities.

Asarco, in its filed answer, specifically denied those charges.

The NLRB hearings are scheduled to continue weekly until mid-November, restart in January and run until early March.

Talks resume

Meanwhile, the Steelworkers union in late July announced that it was back at the bargaining table with Asarco and the sides had already traded initial proposals and reached a tentative agreement on four issues.

“Significant changes have occurred in the industry since the unions and the company last met for (basic labor agreement) negotiations in late 2019,” the Steelworkers said at the time.

Copper prices have soared since early 2020, with spot prices rising from just over $2 in March 2020 to top $4 a year later. Prices averaged nearly $4.25 per pound during 2021 and nearly hit $5 in February, and after dropping to around $3.25 in July has recently been trading above $3.50.

And though the NLRB testimony indicates its workforce is down from 2018, Asarco is hiring now, with 78 open positions listed on its online jobs site last week, including many traditional union trades.

ICYMI: Watch the Star's top videos from the past week

New Javelina Statue unveiled along River path

Updateda new art sculpture was unveiled along the river path near Campbell Avenue. The statue features a javelina on a bike with an extra seat behind for the community to interact and sit on. Video by Pascal Albright/ Arizona Daily Star

Student led rally about school safety at the University of Arizona

UpdatedAbout 40 students and supporters showed up in front of Old Main to rally for change in school policies and administration on the University of Arizona campus, May 4. Video by Pascal Albright / Arizona Daily Star

New Mural highlights wildlife along River Walk

UpdatedA new mural is bringing color to the river walk. The new mural located near country club features vibrant depictions of Arizona wildlife. Video by Pascal Albright / Arizona Daily Star

Pima County Board of Supervisors discusses end of Title 42

UpdatedWatch now: Pima County is preparing to receive an increased number of asylum seekers when Title 42 ends on May 11. Video courtesy of Pima County

ChronicCon is canceled

UpdatedChronicCon, which had been scheduled for May 20th out at Cocoroque Ranch and Pavilion, has been canceled due to a reorganization of the Arizona Daily Star.

Forest Service officials looking for suspect in wildfire on Mount Lemmon

UpdatedForest Service Fire Investigators are trying to identify a man seen on video shooting a gun where the Molino basin wildfire started April 30. Officials are asking anyone with information to call 520-388-8343 or email the Coronado National Forest at Mailroom_R3_Coronado@usda.gov. Video courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service.

A trip to Tucson's year-round farmers market at Rillito Park

UpdatedHeirloom Farmer Markets' weekly offerings at Rillito Park near the Chuck Huckelberry Loop can be found every Sunday morning. The market's current hours are 8 a.m. to noon.

Tucson police release video of fatal March 3 shootout

UpdatedAaron Martinka, 28, was shot and killed by Tucson police after firing at them during a traffic stop near North Campbell Avenue and East Grant Road, authorities say. Video courtesy of the Pima Regional Critical Incident Team.

Take a tour of the Blue Moon Community Garden

UpdatedBlue Moon Community Garden is one of 17 gardens overseen by the nonprofit Community Gardens of Tucson. Through regular events for gardeners and neighbors, CGT aims to bring people together to grow not only healthy foods, but also relationships. Video by Caitlin Schmidt / Arizona Daily Star

Rep. Stahl Hamilton apologizes for hiding copies of the Bible

UpdatedRep. Stephanie Stahl Hamilton, D-Tucson, apologized Wednesday to colleagues for moving and hiding copies of the Bible in the House members’ lounge, saying she was trying to make a “playful” point about the separation of church and state. Video courtesy of Arizona Capitol Television.

Arizona lawmakers propose bill to limit access to online pornography

UpdatedAfter being initially shot down, a new version of State Bill 1503, is being considered by Arizona lawmakers. Video courtesy of Arizona Capitol Television.

President of TUSD board voices support for LGBTQ+ students and staff

UpdatedTucson Unified School District's Governing Board President Ravi Shah spoke in support of LGBTQ+ students and district staff members during a board meeting Tuesday. Shah also showed support for an upcoming student-led drag show at Tucson High.

Footage shows Rep. Stahl Hamilton moving Bibles

UpdatedRep. Stephanie Stahl Hamilton, D-Tucson, was recently filmed hiding copies of the Bible inside a state Capitol lounge. Video courtesy of the Arizona House of Representatives.

Mountain lion caught on doorbell camera outside Bisbee home

UpdatedA mountain lion was recently seen in Bisbee on the porch of a home about 80 miles southeast of Tucson. The Arizona Game and Fish Department asks that sightings are reported at 623-236-7201 so officials can track the movement and behavior of wildlife. Video courtesy of AZGFD.

Time lapse: Northern Lights seen over Tucson

UpdatedThis footage showing the aurora borealis was captured by a camera belonging to the NASA-funded Catalina Sky Survey at Mount Bigelow on April 23 from sundown to about 10 p.m. Video courtesy of David Rankin.

Trail camera catches a busy beaver on the San Pedro River

UpdatedThe river's beaver population is hanging on almost 25 years after being reintroduced by wildlife officials.