Building two plants to purify Gulf of California seawater would supply the annual equivalent of about 16% of the water Arizona will get from the CAP this year — for nearly $5 billion in construction costs.

Pulling most of the salt from ocean water would use much more electricity than more conventional means of supplying water, generating climate-heating greenhouse gases in a region whose temperatures have already risen substantially due to global warming.

Desalination also could put tens of millions of gallons of potentially toxic brine wastewater from the process into the gulf, also known as the Sea of Cortez, which the late naturalist Jacques Yves-Cousteau called “the world’s aquarium.” It’s also a UNESCO World Heritage site due to its rich biological diversity.

Those issues and more are being raised by critics of Gov. Doug Ducey’s new proposal for Arizona taxpayers to spend $1.16 billion in the coming three years as a downpayment toward building desalination plants and other water infrastructure.

Their comments highlight a growing debate about desalination that has spread worldwide with the technology: Is it worth its cost, energy use and potential environmental headaches?

The governor and the plan’s supporters say the proposal offers Arizona a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to realize a long-discussed dream of turning salt water into drinking water. It’s a chance “for Arizona to be a global leader” in finding new water supplies and treating salt water, said C.J. Karamargin, Ducey’s press aide.

“Desalination is not a new concept, (but) we believe it is a concept whose time has come for Arizona. The technology associated with this has been improved tremendously, and all sort of projects are being used around the world. It’s irresponsible to factor into planning Arizona’s water future without taking into account a technology with a proven track record,” Karamargin said.

In Ducey's January 10 "State of the State" address, the governor said, “With resources available in our budget, a relationship with Mexico that we’ve built and strengthened over the last seven years, and the need is clear – what better place to invest more. Instead of just talking about desalination – the technology that made Israel the world’s water superpower – how about we pave the way to make it actually happen."

The critics say the proposal goes too far too fast, while neglecting a host of other water problems and less costly solutions that need addressing first.

For instance, while Arizona has touted its nationally recognized groundwater law governing urban areas, it’s done nothing to regulate rural groundwater pumping that’s draining aquifers from Cochise County to La Paz County, the critics note.

It’s also failed to rein in suburban sprawl in Pima, Maricopa and Pinal counties that relies on pumped groundwater that is supposedly replenished by recharging Central Arizona Project water tens of miles away, they say. The CAP delivers Colorado River water via canals.

“We have to start taking care of our own house before we can be asking people to put money into new supplies,” said Kathy Ferris, a former Arizona Department of Water Resources director and an Arizona State University research fellow. “We’re not doing that. It’s too hard to say no, too hard to say we’re not going to do business as usual. Instead of trying to clean house, it’s easier to say we will go out and find more water and keep doing what we’ve been doing.”

Nationally, the academic community is split on desalination, with some researchers strongly advocating it while others are more cautious. The Arizona Daily Star talked to four water researchers last week. Three said the state should spend money on treating wastewater to drink before desalinating seawater.

Amy Childress, a civil-environmental engineering professor at the University of Southern California, has spent 20 years researching various processes using membranes for desalination, wastewater reclamation and water treatment in general. Asked about the potential for desalination by Arizona, she said, "I guess the key thing is, before going to ocean water desalination, qe have to ask have we done all the conserving we can do? Have we maximized wastewater reuse? Are there are opportunities to import that could be easier?

"I didn’t hear that whole plan out of the Arizona governor. I just heard something that seems like a quick fix, and I don’t think his plan is a quick fix," Childress said.

The fourth researcher, Peter Fiske, who runs a federally funded desalination research institute in Berkeley, California, said the state should first desalinate some of Arizona’s plentiful brackish groundwater supplies spanning from Yuma to the state’s far northeast corner, before taking on seawater desalination.

The reason is seawater desalination’s higher cost and energy use, the four researchers say.

The University of Arizona’s Andrea Achilli worked on a newly published study, with Emily Tow of Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts, that concludes desalinating seawater uses at least twice as much energy as do any of five methods of treating wastewater to drink, as well as treating brackish groundwater.

“The more salty the water, the more expensive it is, the more energy intensive it is,” said Achilli, an assistant chemical and environmental engineering professor. “Desalination is a very mature technology. ... We are not going to see it get much cheaper than what it is currently is. Desalination has its place, but it should be done after we exhaust all the less expensive water reuse options.”.

Tow, also an assistant professor, said that after spending a decade researching how to improve energy efficiency in desalination, she believes the best course is to desalinate less salty, treated municipal sewage effluent to drinking quality.

“Look at the amount of wastewater produced — you can get about 80% of that back as drinkable water,” far more than the percentage of drinkable water from desalting seawater, Tow said.

But just a few years ago, people would say the same thing about solar energy — “we will never get the cost down, and now look,” Karamargin responded.

“Drive down Country Club between Speedway and Broadway. You’ll see a synagogue and a church that have solar panels in their parking lots. Drive by Santa Rita High School, and you’ll see solar panels. Go to an old neighborhood and you’ll see the reflection of the Arizona sun on the roofs,” the Ducey spokesman said.

“Thinking big requires not being bound by old thinking. How do we know what technological improvements that have already been made in desalination won’t continue in a way we can’t fathom?”

Karamargin said there ultimately will be plans for the state to do far more than desalination, taking some of the critics’ suggestions into account.

“Their concerns are certainly real and those types of things will be part of this,” he said, particularly reuse and water efficiency measures. “When I say ‘an all of the above strategy’ it includes items just like that.”

He declined to say when such items will be made public, but added, “Discussions are underway as we speak, with our partners in the Arizona Legislature. They are integral to this.”

Technically feasible

The idea of desalinating Gulf of California seawater dates to the middle to late 1960s. Interest in Arizona has picked up during the past decade as Colorado River supplies shrank.

Now, a 772-page study of a desalination plan for the area, completed in June 2020, is getting widely circulated and a followup study is about to begin.

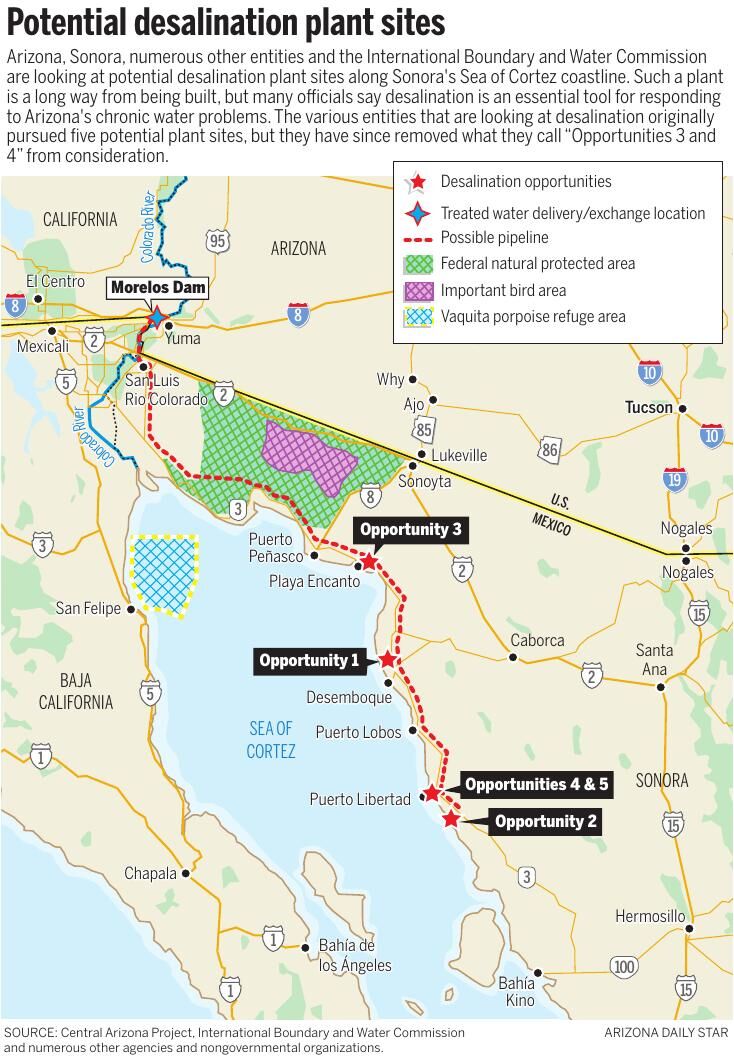

The study examined five potential plant sites in Sonora, from the heavily visited Puerto Peñasco area on the north, to the small town of Puerto Libertad, about 135 miles south. It recommended three of the sites for further consideration, none lying farther north than the tiny community of Jaguey, halfway between Puerto Peñasco and Puerto Libertad.

It was prepared by private consultants under the direction of 18 entities, mostly federal and state agencies in both the United States and Mexico, including the CAP.

A worker passes rows of tubes used in the reverse osmosis process at the Carlsbad Desalination Project in Carlsbad, California.

The study said building plants at any two of these three sites would cost $4.5 billion to $4.9 billion. The plants would use by far the most common desalination technology, reverse osmosis. It uses a semi-permeable membrane to remove salts. Typically, it recovers 35% to 50% from the original seawater as drinkable fresh water.

Desalinated water would be transmitted by pipeline up to 300 miles to the northwest, to Morelos Dam in Sonora, near the border with the United States. From there, it would be distributed to northern Sonora farmers.

The leftover brine would be dispersed off the coast, and the 2020 study concluded that could be done and in most cases meet draft Mexican government standards for salinity levels.

In return, Arizona would gain 200,000 acre-feet — twice what Tucson Water delivers to homes and businesses in a typical year — of Mexico’s 1.5 million acre-foot share of Colorado River water.

No one knows how long it would take to get the plants permitted and built, not least because construction would need approval from a host of Sonoran and Mexican government agencies. Ultimately, the plants would have to be approved by the International Boundary and Water Commission in the U.S. and its Mexican counterpart, commonly known as CILA.

A crucial step is for the two countries to set up a formal legal procedure known as an “exchange framework” that allows them to exchange the desalted water for the Colorado River water. That step may be as far off as 2026.

Arizona officials have said it could take 7 to 10 years to get a plant online, while skeptics say it could take much longer.

When CAP officials discussed the study at a board meeting in October, they said the plants’ cost translates to about $2,000 an acre-foot, That’s slightly more than 10 times what CAP charges Tucson and Phoenix-area customers for drinking water. It’s also consistent with costs of major desalination plants in the Middle East, CAP officials said.

CAP board is split

CAP Board President Terry Goddard counts himself a skeptic of seawater desalination, in large part because of its cost.

“Say we say OK, we go ahead with it. Twenty years from now … who wants that water? In 20 years, it may be a hot commodity. But right now, I don’t think there are any takers.”

“Boy, at that price, there were lots of other options out there,” Goddard said.

For one, there’s the purification of municipal wastewater for drinking, which is now being done in California’s Orange and San Diego counties. In Arizona, Scottsdale is treating its wastewater to drinking quality but isn’t serving it to water users yet. The city is recharging it into the aquifer for storage and possible future use.

Estimates from the state are that 93% of Arizona’s sewage effluent is already being reused, either to irrigate golf courses and parks, to discharge into rivers such as the Santa Cruz in Tucson to recharge the aquifer, or to provide cooling water for the Palo Verde Nuclear Plant outside Phoenix.

Using that water for drinking would thereby deprive other uses, and could be controversial, particularly if large amounts of effluent now running down and providing wildlife habitat in the Santa Cruz here is converted to drinking water.

There’s also a proposal to raise the elevation of a major dam on the Verde River north of Phoenix, to store more water for urban customers, Goddard noted.

Another option is the brackish groundwater, which is particularly prevalent in Buckeye and is far less salty than seawater. One estimate, cited in 2015 by the consulting firm Montgomery and Associates, is that the state has 600 million acre-feet of brackish groundwater. That’s enough for about 500 years of CAP deliveries at the project’s current pace. CAP ia scheduled to deliver about 1.2 million acre feet of Colorado River water this year to cities and farmers, the CAP agency's records show.

CAP board member Alexandra Arboleda of Phoenix is more favorably inclined to Mexican desalination.

“If you are blending some really expensive water with less expensive water, your overall price will not go up as much,” she said. “It’s not like all water will cost $2,000 an acre-foot.”

In 2019, Arboleda accompanied other CAP board members on a weeklong trip to Israel to tour that country’s desalination plans and attend several discussions on desalination.

“I was really, actually impressed with the way they are doing that,” she said of the Israelis, noting that their only freshwater supply comes from the Jordan River.

“If you compare (Mexican desalination) to building a pipeline from the Missouri or Mississippi rivers, it seems a little bit more viable,” she said.

The Carlsbad, California, desalination plant, which borders Interstate 5 on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other, is America’s largest seawater desalination plant. It opened in 2015 and produces drinking water for the San Diego area.

Last year, Arizona’s Legislature appropriated $160 million for what it called a drought mitigation fund, to pay some of the costs of a possible future water importation project such a pipeline from the Mississippi or Missouri rivers.

Conservation issue

Arboleda agrees with others, however, who say Arizona also needs to do more to conserve water.

Last month, at a Colorado River conference in Las Vegas, she was impressed by a presentation by a Southern Nevada Water Authority official itemizing far-reaching conservation measures there.

On top of the authority’s having paid homeowners to remove enough grass since 1999 to cover 3,472 football fields, its deputy general manager Colby Pellegrino cited recent Nevada legislation banning Colorado River water on nonfunctional turf by 2027, on all but single-family home lots.

The Las Vegas Valley Water District no longer provides municipal water to golf courses within its boundaries, Arboleda noted. The district also won’t provide water to homes on septic tanks because that water can’t be further treated and reused. Other proposals would limit pool sizes and restrict turf in new developments except parks and schools.

“If you’re considering spending billions of dollars on a new water supply that’s going to take a decade or some decades to come to fruition, you need to compare it to how much does it cost you per acre-foot for conservation,” said Gary Woodard, a retired UA research faculty member who is now a private water consultant.

“You can start it right now. You don’t have to have good relations with Mexico. You can do it as much as you want, start it or stop it or resume it,” he said.

UA professor Margaret Wilder, who co-authored a 2016 study on Sonoran desalination issues, calls herself “very much a skeptic of these plants.”

She says Ducey’s push is “way premature. I think they are overselling it and oversimplifying it. I think they are willing to sacrifice the Sea of Cortez. That’s very shortsighted, given the crisis the oceans are in.”

Today, authorities don’t know how the brine will behave in a particular body of water. It depends on currents, atmospheric conditions, wave structures, she said.

“There are environmental consequences, political issues and issues of equity with Mexico and how local communities and the country as a whole will fare,” Wilder added. “There are a lot of economic interests at play that are potentially overwhelming environmental concerns.”

Tucson official receptive to plan

Tucson Assistant City Manager Tim Thomure and Arizona Municipal Water Users Association General Manager Warren Tenney are receptive to Ducey’s proposal.

“I feel that it is a positive development to have the governor and the Legislature looking at how to invest into our water future,” said Tenney, a former Metro Water general manager in Tucson.

“Anything that we do regarding our water future, it’s important. It can’t be done by just one city at a time. We also need backing of the state.

“Desal certainly needs to be looked at, whether or how it will best benefit Arizona. A lot of questions need to be answered about desalination. If a billion dollars helps us get the answers, that would be great,” Tenney added.

A state-financed desalination plant in which Arizona would get some of Mexico or California’s Colorado River water supplies via the CAP is a viable long-term water supply, Thomure said.

"The idea has been around since at least 1968 that I am aware of. More recent groundwork has been in process since 2009 and the idea is gaining momentum. Note that there are other near-term, pragmatic solutions that can and should be pursued with as much vigor as ocean desal," said Thomure.

A supply like that could help Tucson make its water supplies more resilient or even be used to replace other supplies in the future, he said. However, Thomure said that time is likely distant because the city has a healthy water portfolio today that exceeds the demand that’s projected “for decades ahead.”

Tucson would expect to pay a substantially higher rate for additional water beyond CAP supplies from desalination, he said. But the city would also expect to have the choice of taking water available due to desalination and “only pay to the degree we benefit.”

The inside of an El Paso desalination plant, where brine passes through tubes with coiled membranes to make water drinkable.

“We would not expect to subsidize the project or water cost for the benefit of others,” he said.

Some of Tucson's conditions for supporting an actual plant project would be would include environmental protections associated with the plant itself, such as proper design to minimize the "entrainment," or trapping and killing of aquatic life, and proper reintroduction of the brine waste steam to the sea or ocean, he said.

"Further, we would have concerns over social and environmental justice at the plant site, including fair labor practices, equitable access to the water, avoidance of noise and pollution impacts to the local community, and others," who noted that I believe it would be Tucson’s position that we do not intend to extract benefits for our community that cause social or environmental costs borne by others, said Thomure, adding that these comments represent only his opinion because Mayor Regina Romero and the City Council haven't weighed in on this issue.