A local right-to-die organization has been resurrected under a new name after a rift with its parent group over the death of a Tucson woman last year.

John Abraham, longtime death-with-dignity advocate, said he officially launched the new group, called Choice and Dignity, last week after the nonprofit Final Exit Network announced plans late last year to shut down its handful of affiliates nationwide amid liability concerns.

Abraham said the mission of the new organization is the same as the old one: to advocate for and provide information to people seeking “self-deliverance” from intolerable suffering or end-of-life pain.

“Of the people who come to us, very few hasten their own deaths,” he said. “Infinitely more are comforted by knowing they have a way out if they need it.”

Final Exit Network operated in Southern Arizona for more than a decade, and Abraham served as the local chapter’s leader starting in 2014.

Brian Ruder, board president for the network, said the decision to shut down the affiliates was prompted, at least in part, by the death of a Tucson woman with a degenerative disease who sought the group’s services but later ended her life “without going through our process.”

Ruder and Abraham declined to name the woman in question, but both said her death went exactly as she planned it. The problem arose afterward, when her spouse complained that she chose to end her life over his objections.

“The thing that we are most concerned about is that the family understands the decision and supports it,” Ruder said.

Abraham said he wants that too, but the final choice always rests with the individual. “Get all the input you can. That’s great, but ultimately the decision is yours,” he said. “My belief lies in individual autonomy.”

Ruder said Final Exit can’t afford to take chances like that.

“What we find is there are people out there who would like to take our organization down,” he said. “We try very hard to be as pure as possible, because we don’t want anyone to be able to say that we’re doing this for any other reason than we think it’s a right for people who qualify to be able to end their lives on their terms.”

The 15-year-old nonprofit only had three affiliates. Ruder said the Tucson one was the most active by far, thanks to Abraham’s efforts. “John’s taken it to another level,” he said. “To some degree, Final Exit was holding him back. We thought it was time for him to go off and do his own thing.”

Dr. Jack Kevorkian sparked the national right-to-die debate in the 1990s. He spent time in prison after “60 Minutes” aired a video of him giving a lethal injection to a man in 1998.

“Where Kevorkian got in trouble”

Abraham doesn’t refer to what he does as assisted suicide. It’s “deliberate life completion,” he said, and his group provides “support, not help.”

Though Abraham claims the right-to-die movement’s largest institutional opponent is the Catholic Church, there is widespread opposition to the practice that has nothing to do with religious belief.

Some doctors and medical ethicists note that only a small percentage of those who seek physician-assisted suicide are terminally ill patients with uncontrollable pain. Instead the decision is often driven by depression, hopelessness and psychological distress — conditions usually treated with psychiatric intervention, not lethal doses of medication or deadly gases.

Eight states and the District of Columbia now allow physician-assisted suicide, also known as medical aid in dying, under specific circumstances, but Abraham said even those laws don’t go far enough. They only apply to terminally ill patients in their last few months of life, not those with degenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease or multiple sclerosis that are incurable but indeterminate.

“They need to terminate the terminal from the law. It’s too restrictive,” he said.

Those looking to end their lives in states where it is legal can also struggle to find doctors willing to provide the service or get hit with sizable bills for consultation and medication, Abraham said.

He’s heard of people having to pay as much as $10,000 just to die, whereas the method promoted by his group and others involves roughly $500 for the mask, inert gas, tubing and other equipment.

Arizona has no assisted suicide laws. Under state statute, a person can be charged with manslaughter for “intentionally providing the physical means that another person uses to commit suicide, with the knowledge that the person intends to commit suicide.”

That’s why Abraham said he is careful to only provide information and support to qualified individuals who seek his help, namely mentally competent people who can voluntarily and repeatedly articulate their reasons for so-called “self-deliverance” from the existential pain of a hopeless illness.

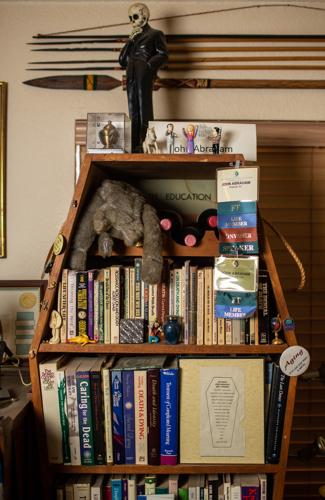

A coffin-shaped bookshelf in John Abraham’s home. Abraham said he made all his own arrangements over a decade ago.

“There’s nothing illegal about giving information,” he said. “There’s nothing illegal about being with someone when they die. You just have to make sure your fingerprints aren’t on the hood or any of the equipment.”

“That’s where (Dr. Jack) Kevorkian got in trouble,” Abraham added. “He went too far. He pushed the button.”

Done lobbying at the Legislature

Choice and Dignity members met on Feb. 4 to select an eight-person board of directors, approve bylaws and settle on the organization’s name, logo and color scheme — sort of a blue-green with dark lettering.

The end-of-life advocacy group already has 44 members and a possible bequest from a woman who contacted Abraham on Tuesday and offered to write Choice and Dignity into her will.

“I hear from people all over the world. I don’t know how the hell they find me, but they do,” he said.

On March 4, Choice and Dignity will hold a free introductory meeting at 1:30 p.m. at Total Wine and More’s Park Place mall location on East Broadway.

The organization has also scheduled a series of small discussion groups, end-of-life advocacy training sessions, workshops on preparing advanced medical directives, and something called a Life Completion Class, at which Abraham plans to demonstrate such self-deliverance methods as asphyxiation with nitrogen or helium.

Lobbying state lawmakers will not be part of the new group’s mission.

Though Abraham said he supports changes to the law, he said he’s done actively campaigning for them.

“That kind of legislation has been introduced every year for the last 30 years in Arizona. It never makes it out of committee. It’s never going to pass in my lifetime, not with this Legislature. It’s an exercise in futility.”

Activist prepared for his own death

Death is a big part of Abraham’s life these days. He has surrounded himself with it.

His modest tract home in Marana is cluttered with books and posters and promotional materials on the subject. On a coffee table shaped like the lid of a coffin, there is a wooden bowl filled with buttons that read, “Let Me Die Like a Dog.”

Abraham answers the front door in a sweatshirt advertising “suffer busters,” a euphemism for the service he provides.

He opens his garage door to reveal what he calls the “death mobile,” a Mazda hatchback decorated with Final Exit magnetic signs and novelty plates that read “CHOYCES” and “WEALLDI.”

Abraham said he has been helping people with end-of-life issues his entire adult life, first as an Episcopal priest and then in hospice care, where he has held every job “from president to bedpan changer.”

“I’ve seen people die every which way you can imagine,” he said. “I thought there’s gotta be a better way.”

Abraham joined the right-to-die movement 30 years ago and became a full-time volunteer for the cause in 2013.

He said he has attended 77 deaths and consulted on 100 or more since 1980, including about 60 in the Tucson area.

In 2017, he compiled his knowledge and experience in a book called “How To Get The Death You Want: A Practical And Moral Guide.”

For his part, the 72-year-old said he made all his own arrangements more than a decade ago.

First he drafted advanced directives to guide his end-of-life medical care, then he lined up a strong advocate to see that those directives are followed when the time comes. And should he need to speed things along, he said he’s already got the necessary equipment all lined up.

Abraham is under no illusions about what’s coming. He has been a pack-a-day smoker since he was a teenager, and he’s got the cough to prove it.

“Death is a natural part of life. Everything begins and ends eventually,” he said with a wave of his cigarette. “I’m stupid enough to die one coffin nail at a time.”