A state water board unanimously agreed Tuesday to start discussions with a giant Israeli company over its proposal to build a $5.5 billion seawater desalination plant on the Sonoran coast and sell desalted water to Arizona users.

If such a plant were ultimately approved and built, a final signoff by this board, which is a ways off, would commit the state to providing financial backup toward repaying the construction cost if the plant can’t sell enough water to customers in Arizona and Sonora to cover all those costs.

Brushing aside complaints from some citizens that it’s moving too fast, the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority’s governing board voted 9-0 to take the first step toward clearing the way for construction of such a plant, while acknowledging that many issues about its cost and potential environmental impacts need further discussion and negotiation.

It will be the first project to receive serious consideration by the board since the Arizona Legislature agreed this spring to give the board $1 billion over three years and legal authority to approve major projects aimed at augmenting, or increasing, Arizona’s now-fragile water supplies. This plant, whose backers say could be online by 2027, would be aimed at supplementing supplies now provided by the Colorado River that are slowly disappearing due to long-term drought and climate change.

“This project, if it goes forward, would not foreclose other projects over the long term,” board chairman David Beckham said just before the votes were cast. “We want to make sure there’s all sorts of projects. I look forward to seeing other proposals in the future from the long-term augmentation fund.”

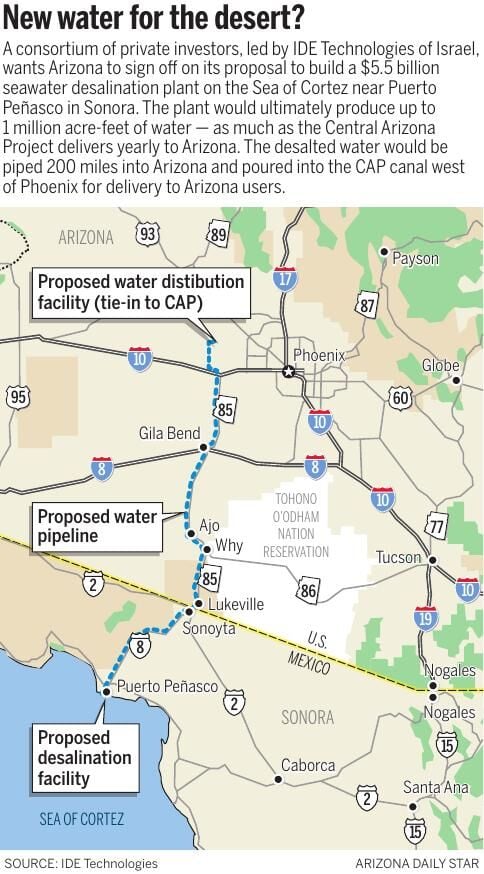

IDE Technologies of Israel is proposing to build what would be the world’s largest seawater desalination plant in the area of Sonoran beach resort Puerto Peñasco. The proposal calls for delivering the desalinated water north to the Phoenix area via a 200-mile-long pipeline. It would connect to the Central Arizona Project canal system west of Phoenix, so the water could be distributed to cities and towns that wish to buy rights to it.

Discussion and debate about this project came to the new board before it hires an executive director and before it draws up procedures for determining the kinds of augmentation projects to support.

As company officials describe the proposal, the plant would at first provide 300,000 acre-feet of desalted water from the Sea of Cortez. That would be almost enough water to serve all of Tucson Water’s customers for three years.

Ultimately, company officials say they hope to expand the plant enough to produce about 1 million acre-feet of fresh water. That’s about how much water the 336-mile-long CAP canal system delivered this year and is scheduled to deliver next year to Phoenix, Tucson and smaller Southern and Central Arizona cities.

In fact, a promotional video company officials played at Tuesday’s board meeting said of the pipeline, “You may call it an inverse and permanent Colorado River,” the source of CAP’s water.

Arizona wouldn’t get all the desalinated water. Some would go to the Sonoran cities of Hermosillo, Puerto Peñasco, Sonoyta and Nogales, company officials said.

The company and other investors in the project would pay all its up-front construction costs, IDE officials told the board. Then, water customers in cities that ultimately sign up for the desalted water would help repay the construction cost by buying the water.

The state water infrastructure board would be asked to provide what’s called “credit support” in the way of financial backing for the project. If the state provides credit support, that means it would guarantee it will put up money to cover any costs of the project that aren’t covered by water bills paid by customers.

Depending on several factors, it would cost anywhere from $2,200 to $3,300 an acre-foot for the plant to produce the desalinated water. But in the end, since the desalted water cost would be mixed in with other lesser costs charged by local water utilities, that cost would translate to no more than a few dollars more a month in water bills than people are currently paying, IDE officials said.

Tuesday’s approval is just the start of a long list of government approvals a project of this scale will need. On Wednesday, Dec. 21, IDE officials will submit a proposal to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management for the agency to prepare a detailed environmental analysis of the project, whose pipeline would go through some federal land.

The plant will also need permits from other U.S. and Mexican agencies. But the company hopes to have permitting completed in two years and construction work done in another three years to allow for a 2027 start for delivering the water, said Eres Hota, leader of IDE’s team overseeing the proposal.

Critics of the speed at which this project is being processed said the water infrastructure board has been unduly rushed into agreeing even to formally negotiate a set of terms for the company to build and operate the plant.

“I’m upset. We tried to insure that this WIFA board could not rubber-stamp a project, and now we see a potentially problematic desal plant move forward,” said Sen. Lisa Otondo, a Yuma Democrat who helped craft the compromise legislation earlier this year that gave the infrastructure board the authority and financing to tackle such large augmentation projects. “They still haven’t established guiding principles for augmentation, and there’s a severe lack of water policy knowledge at the agency.”

At $3,000 an acre-foot, selling a million acre-feet of water a year will cost $3 billion year, “and what water customers are going to pay $3 billion for raw, untreated, desalinated water?” Otondo said.

Karl Flessa, a University of Arizona retired geosciences professor who has studied the Colorado River’s ecology for 30 years, said the push for this project “seems to be an effort to get priority for consideration of this proposal without adequate review of the technology.”

“It will scare away competing proposals. At best, this resolution is premature. It commits (the authority) to provide its staff to very substantial efforts to clear enormous hurdles facing this project,” Flessa told the board. “Approval of this project will, I fear, damage the credibility” of the authority, he said.

But Joe Gysel, president of the private water company Epcor, endorsed the idea of having the state agency start negotiating with the desalination company quickly.

“The timeline on these projects is very extended. If you do not begin your evaluation, you will not be able to augment. This project will take a minimum of 10 years. Delay is not on our side, given the drastic situation of the Colorado River. We will rely on the board and its expertise to make sure this is the best project for augmentation,” Gysel said.

IDE Technologies has built many desalination plants in Israel and says it is providing water security for that country.

Photos: Central Arizona Project canal construction in 1979

Construction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

6/9/1979 Central Arizona Project construction. Photo by Joan Rennick / CitizenConstruction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

6/9/1979 Central Arizona Project construction. Photo by Joan Rennick / CitizenConstruction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

Construction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

6/9/1979 Central Arizona Project construction. Construction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

6/9/1979 Central Arizona Project construction. Photo by Joan Rennick / CitizenConstruction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

Construction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

Construction of the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct in Western Arizona in June, 1979. The canal supplies the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas with Colorado River water.

As water in one of the nation's largest reservoirs recedes, geologic features hidden for nearly 50 years are revealed in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area in Northern Arizona. Video courtesy of Glen Canyon Institute, 2022