Tucson was a much smaller place the last time it was turned upside down by a global pandemic.

In 1918, the city covered less than 8 square miles and was home to fewer than 20,000 people.

When residents started to die that spring from a devastating new strain of the flu, the virus didn’t even have a name yet.

What came to be known as Spanish influenza did most of its damage during the fall of 1918, but researchers believe it was already in wide circulation earlier that year, spawning deadly pneumonia in children under 5, seniors 65 and older and a shocking number of otherwise healthy adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

The virus would go on to infect some 500 million people, roughly one-third of the world’s population at the time. At least 50 million people died, including an estimated 675,000 in the United States.

According to some estimates, almost 1% of Arizona’s population was wiped out by the 1918 pandemic. Several hundred of them were Tucsonans. Many of the dead were young adults, struck down in the prime of their lives.

“That was the most intense outbreak of infectious disease in human history,” said Michael Worobey, who heads up the University of Arizona’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “It killed tens of millions of people in a matter of weeks.”

worst luck humans ever experienced

Research by Worobey, an evolutionary biologist who studies the origins of viruses like Spanish influenza and COVID-19, is shedding light on the 100-year-old mystery of why the 1918 outbreak killed so many young adults in the prime of life.

People in their 20s and 30s proved particularly vulnerable to the virus because of a tendency by the human immune system to imprint on the first strain of influenza A encountered during childhood, then produce similar antibodies to fight all future flu infections, Worobey said.

For many young adults in 1918, the first flu they were exposed to as children was “as different as it could be from Spanish flu,” leaving them with a hard-wired immune response that was ineffective against the pandemic.

There is an incredible name for this phenomenon, coined over 60 years ago by Thomas Francis Jr., a prominent American virologist whose father was a part-time minister. Francis called it, “The doctrine of original antigenic sin.”

Worobey said the problem was made worse by World War I, which brought together whole armies of young adults from around the globe. Thousands survived the fighting only to die of the flu.

Then, once the war was over, all those soldiers crowded back aboard their transport ships and returned home to America, touching off a fresh wave of infection in late 1918.

Add up all those factors — the immune system vulnerability, the perfect virus to exploit it, a global war and an armistice — and what you do you get? “Probably the worst luck human beings have ever experienced,” Worobey said.

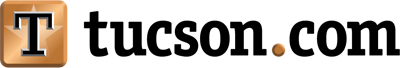

Volunteer nurses from the American Red Cross tend to Spanish influenza patients in the Oakland Municipal Auditorium, which was used as a temporary hospital in Oakland, California, in 1918.

Some lost several loved ones within days

It’s impossible to know exactly how many Tucsonans were killed by the Spanish flu. With no tissue samples from back then to examine under a microscope, the best you can do is estimate using available public records and other evidence.

Research archaeologist Homer Thiel recently reviewed Pima County’s vital statistics from that time and read through every death certificate issued between July 1918 and June 1919 looking for signs of the pandemic.

One particular spike is easy enough to see. In 1917, there were 682 deaths recorded in the county. The following year, that number jumped to 927, and included an unusually large number of young adults.

The common causes of death are also telling.

“If you go look at the 1918 death certificates, you’ll see lots of examples of bronchial pneumonia,” said Thiel, who works for the Tucson-based consulting firm Desert Archaeology. “Clearly October 1918 through January 1919 were the worst months.”

Based on his analysis, he estimates just over 300 people died from Spanish influenza over the course of one year, roughly 1% of the county’s population.

And that’s just the obvious cases.

Death certificates weren’t issued for some people, especially those living far from major settlements. And Thiel suspects some deaths that were blamed on tuberculosis at that time might have been caused — or at least exacerbated — by influenza.

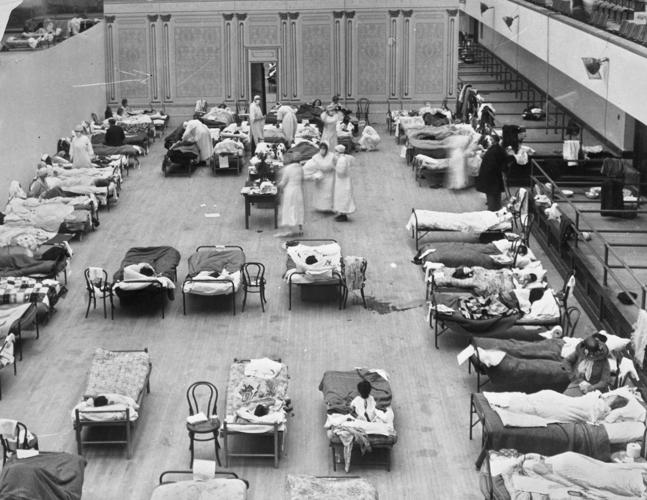

An Arizona Daily Star headline from Oct. 10, 1918, alerts the public to the closing of public places due to the Spanish flu.

The average age of county residents killed by the flu was 25 years. The average length of time they were sick before they died was 7 days, according to his analysis.

Thiel found several families that lost multiple people to the outbreak.

Maria Christine Guerrero, 6, and her sister Dolores Guerrero, 9, died of influenza within nine days of each other in late December of 1918. They were buried side by side at Holy Hope Cemetery, where they were joined more than 50 years later by their parents, Eduardo and Concepcion, who both lived into their mid-80s.

The Drumm family lost three sons in five days in early 1919, all to influenza. Russell, 24, and Glenwood, 26, both died on Jan. 24. Karl, 28, died Jan. 29, two days after his two younger brothers were buried at Evergreen Cemetery.

The “pest house,” other gruesome lessons

The Spanish flu was not Tucson’s first brush with a major disease outbreak.

The region had already lived through several deadly epidemics, as Old World diseases spread northward following the arrival of the Spanish in Mexico.

Waves of successive outbreaks are described in the Spanish-era mission records, with Native American communities among the hardest hit because of their lack of immunity, Thiel said.

“It’s happened over and over again,” he said.

In 1851, an unknown pathogen, probably smallpox, killed 125 people, a quarter of Tucson’s population.

Dozens more died from smallpox in the early 1870s, prompting city leaders to turn a four-room home a mile south of the city limits into a “pest house” for isolating people infected with the disease.

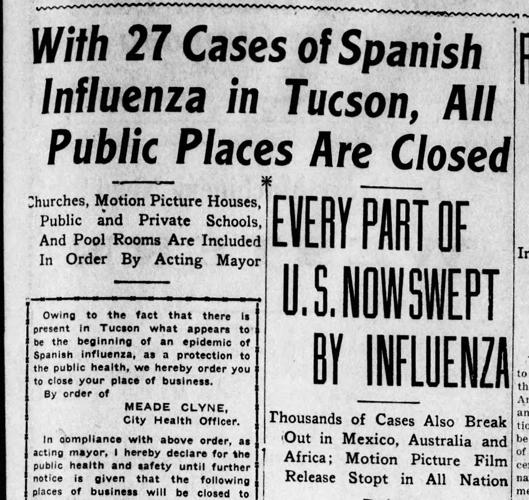

A Nov. 6, 1918, headline in the Tucson Citizen describes the Spanish flu, which killed at least 50 million people worldwide.

The Southern Pacific Railroad was required to examine incoming passengers for evidence of smallpox, and a special wagon was purchased to transport the sick to the pest house, Thiel said. Local residents raised money to purchase clothing and bedding for the unfortunate souls being kept in quarantine.

Eventually, as the city expanded south, people demanded that the pest house be moved to a more distant location, Thiel said. In 1906, a new brick building was constructed north of St. Mary’s Hospital with bars on the windows to prevent patients from escaping.

The pest house also had its own cemetery, and tents would be added on occasion to house excess people during particularly serious outbreaks.

Some of the gruesome lessons learned from earlier epidemics in Tucson were put to use during the Spanish influenza, including disinfecting or closing public spaces, isolating the sick and carefully disposing of their clothing and other possessions after they died, he said.

Thiel has personally excavated abandoned graves in Tucson and found people who were buried with their personal effects still in their pockets and the rest of their clothing tossed in with them, probably to avoid the spread of whatever killed them.

He sees some troubling echoes from the past in the current response to COVID-19.

The 1870 small pox outbreak made headlines outside of Southern Arizona, but the local papers scarcely mentioned it. “People in Tucson, they were keeping it quiet,” he said, because they were afraid of the impact it might have on the reputation of the community and its businesses.

Some world leaders have tried a similar approach to the current pandemic, downplaying it — at least early on — in hopes of limiting some of the economic fallout, he said.

“It’s a repeat of everything that’s happened before,” Thiel said.

Dolores Guerrero, who was 9, and her 6-year-old sister Maria Christina Guerrero died within nine days of each other in December 1918. According to some estimates, almost 1% of Arizona’s population was wiped out by the Spanish influenza.

“We’re Behind where we were in 1918”

Though some evidence suggests the Spanish flu pandemic actually began in North America, scientists still disagree about its exact origins.

The virus got its name because Spain was neutral during the war, leaving its press uncensored and free to report on the sickness when it finally appeared there.

“The one place we know it probably didn’t come from is Spain,” Worobey said.

No one really knew what a virus was back then. There were no antibiotics or ventilators to help treat the afflicted. But some of the things health officials did to try to contain Spanish flu are similar to what’s being done — or in some places, not being done — to slow the spread of COVID-19 today.

“In some cases, we’re behind where we were in 1918,” Worobey said.

For example, protective masks were prevalent — and even mandatory in some places — during the Spanish flu pandemic. “We haven’t been able to manage that in 2020, which is pretty pathetic actually,” Worobey said.

Another similarity between then and now: The communities with the best outcomes tend to be the ones that diagnose the threat early and act right away to isolate it.

In 1918, Worobey said, St. Louis quickly closed its public spaces and minimized human contact to slow the spread of the virus. Philadelphia initially did the opposite, hosting, in the midst of the outbreak, a massive liberty bond parade to support the war effort.

As a result, Philadelphia’s death rate from the virus was more than double the rate in St. Louis.

When the outbreak was finally recognized in Tucson, local officials closed schools and churches, shut down movie theaters and other gathering places, and eventually required masks to be worn on city streets and inside businesses.

But the first of those measures didn’t come until mid-October of 1918, too late for some victims of the virus.

Testing, tracing and taking it seriously

Similar inaction by communities today could carry similar consequences, Worobey said. “A couple of weeks of dithering by New York might cost thousands of a lives.”

For now, he said, widespread closures, stay-at-home orders and strict physical distancing — the same “blunt tools” used 100 years ago — represent the best hope of slowing the coronavirus.

But the only real path out of our current predicament, the only way to keep the virus from flaring back up the moment we all emerge from isolation, is by testing as many people as possible and mapping everyone’s exposure, Worobey said.

“One advantage we have now that we didn’t have in 1918 is we can test for this virus. We still need to make that the goal.”

The first step is for everyone to recognize the seriousness of the situation, Worobey said. COVID-19 is “in the same ballpark as Spanish flu in terms of its ability to kill millions of people around the world,” he said, so officials everywhere need to act accordingly to save as many lives as possible.

“I still have great confidence in what this country can do when it pulls out all the stops. It’s not too late to pull out all the stops and get widespread testing in place,” he said. “I’m thinking if we can put a man on the moon in 1969, maybe we can produce some (testing) swabs quickly in 2020.”